PCOS vs Adrenal Hyperplasia: Androgen Excess Explained

Explore the differences between PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia, their symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options for managing androgen excess in women.

Explore the differences between PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia, their symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options for managing androgen excess in women.

PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia are two leading causes of androgen excess in women, but they differ in origin, symptoms, and treatment.

Key Diagnostic Tools:

Treatment Approaches:

| Aspect | PCOS | Adrenal Hyperplasia |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Insulin resistance, ovarian dysfunction | Genetic enzyme defects (CYP21A2) |

| Primary Androgen Source | Ovaries (with some adrenal involvement) | Adrenal glands |

| Prevalence | 80–90% of hyperandrogenism cases | ~2% of hyperandrogenism cases |

| Symptoms | Irregular periods, infertility, metabolic issues | Hirsutism worsens with age, virilization |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, metformin, contraceptives | Glucocorticoids, genetic counseling |

Proper diagnosis is essential to avoid ineffective or harmful treatments. Hormone testing, imaging, and genetic analysis are critical in distinguishing between these conditions.

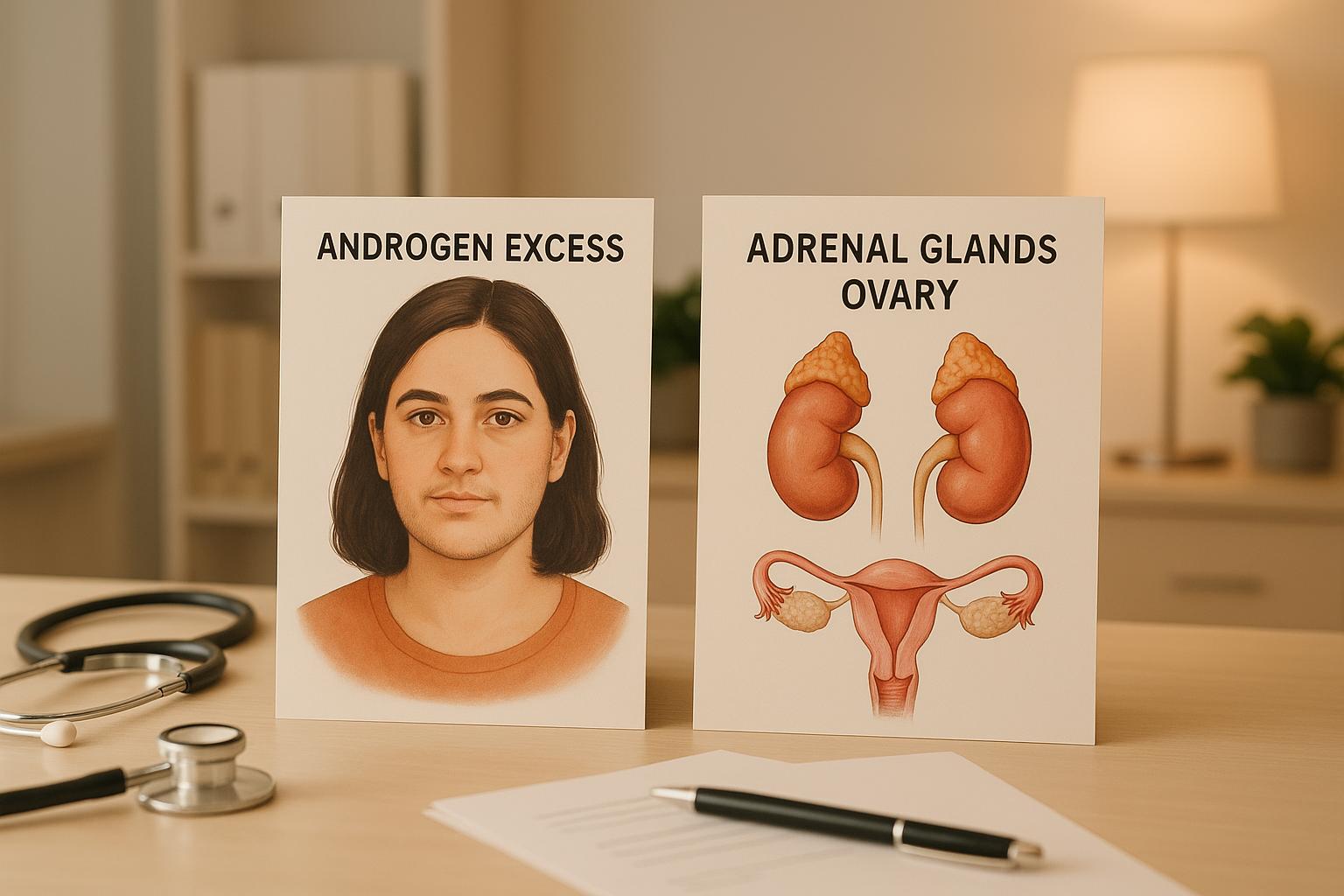

To understand how androgen excess occurs, we need to examine the enzyme systems responsible for hormone production in both PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia. While the mechanisms behind these conditions differ, there are some shared features.

The enzyme P450c17 plays a central role in androgen synthesis. It facilitates the conversion of C21-precursors into 17‑ketosteroids and has two critical functions: 17‑hydroxylase and 17,20‑lyase activities. This enzyme essentially controls the balance between cortisol and testosterone production.

In PCOS, dysregulation of P450c17 in the ovaries and adrenal glands leads to elevated androgen levels. This process is influenced by luteinizing hormone (LH) in the ovaries and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the adrenal glands. This imbalance sets off metabolic changes that further increase androgen production.

In adrenal hyperplasia, genetic mutations disrupt enzyme function, causing abnormal secretion of adrenal hormones. This often results in the development of hyperplasia in the adrenal cortex.

Insulin resistance is a key factor in the androgen excess seen in PCOS. The insulin/IGF system boosts P450c17 mRNA expression and activity in both the ovaries and adrenal glands. Elevated insulin levels, in turn, drive ovarian androgen production.

It’s estimated that 60%–70% of women with PCOS experience insulin resistance. However, as Dr. Kursad Unluhizarci, MD, from Erciyes University Medical School, notes, not all women with PCOS have insulin resistance. In some cases, insulin effects unrelated to metabolism are overexpressed.

In women with PCOS, insulin resistance results in hyperinsulinemia, which amplifies LH-induced androgen production by theca cells in the ovaries. Additionally, serine phosphorylation may connect insulin resistance to hyperandrogenemia by enhancing the 17,20‑lyase activity of P450c17.

Adrenal hyperplasia follows a completely different pathway. Around 95% of congenital adrenal hyperplasia cases are caused by 21‑hydroxylase deficiency. Mutations in the CYP21A2 gene disrupt the production of the 21‑hydroxylase enzyme, which is essential for synthesizing cortisol and aldosterone.

In non‑classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NC‑CAH), these mutations impair the conversion of 17‑OHP to 11‑deoxycortisol, reducing cortisol synthesis. The resulting cortisol deficiency triggers increased ACTH secretion, which overstimulates the adrenal glands and leads to excess androgen production. NC‑CAH is a relatively common autosomal recessive disorder, with prevalence rates ranging from 1:1,000 to 1:2,000, depending on ethnicity.

While PCOS-related enzyme overactivity is primarily driven by insulin resistance, adrenal hyperplasia arises from genetic defects. These differences highlight the distinct origins of androgen excess in the two conditions.

| Aspect | PCOS | Adrenal Hyperplasia |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Insulin resistance + LH stimulation | Genetic enzyme defects |

| Enzyme Activity | P450c17 overactivity | CYP21A2 deficiency |

| Androgen Source | Ovaries and adrenal glands | Primarily adrenal glands |

| Mechanism | Hyperinsulinemia amplifies production | Cortisol deficiency diverts precursors |

The primary distinction lies in the root cause. In PCOS, hyperinsulinemia enhances P450c17 activity, redirecting steroid precursors toward androgen production. In adrenal hyperplasia, the issue stems from defective enzymes caused by genetic mutations.

This overlap in symptoms can make distinguishing between the two conditions challenging, emphasizing the need for accurate diagnostic testing.

PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia may arise from different causes, but both can lead to excess androgen production, resulting in overlapping physical symptoms. Recognizing these shared traits while pinpointing their differences is key to accurate diagnosis.

Both conditions are marked by hyperandrogenism, which drives symptoms like hirsutism - unwanted hair growth on areas such as the face, chest, and back. This affects about 5–10% of women of reproductive age and is often a reason for seeking treatment.

Another common issue is acne, which frequently extends beyond the face to the chest and back. Both conditions share a similar prevalence for this type of hormonal acne.

Additionally, menstrual irregularities - ranging from infrequent periods to a complete lack of menstruation - are typical in both PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia.

These shared features create a foundation for exploring their differences.

Despite their similarities, some differences can help distinguish PCOS from adrenal hyperplasia. For instance, ovulatory dysfunction is a major concern in PCOS, affecting 70–90% of cases, and often leads to more pronounced fertility challenges compared to adrenal hyperplasia.

Metabolic syndrome is another differentiator. It is more severe and widespread in PCOS, while it occurs less frequently and with milder effects in adrenal hyperplasia.

The pattern of hirsutism also varies. In PCOS, hirsutism often diminishes with age. By contrast, in adrenal hyperplasia, it tends to worsen, with about 90% of women over 40 experiencing it.

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for determining the appropriate diagnostic path.

Certain symptoms may point to more severe underlying issues. A sudden onset of severe hirsutism, voice deepening, or male-pattern baldness could indicate an androgen-secreting tumor rather than PCOS. Similarly, virilization signs - like clitoromegaly or voice changes - are rare in both PCOS and mild adrenal hyperplasia but, when present, suggest significant androgen excess. These signs require immediate hormonal testing to rule out more serious conditions.

| Symptom | PCOS | Adrenal Hyperplasia |

|---|---|---|

| Hirsutism | Common; decreases with age | Common; increases with age |

| Acne | Common (14–25%) | Common (33%) |

| Menstrual Irregularities | Very common (90%) | Common (17%) |

| Ovulatory Dysfunction | 70–90% | Less frequent |

| Metabolic Syndrome | Very common and more severe | Less common |

| Virilization | Rare | Possible in severe cases |

| Insulin Resistance | Very common | Present but less severe |

The overlap in symptoms between PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia can make diagnosis tricky. For example, while PCOS is the leading cause of hirsutism, up to 30% of individuals with PCOS also show signs of excess adrenal androgen production, hinting at some level of adrenal involvement. This overlap means that some women might exhibit traits of both conditions.

Adding to the complexity, conditions like Cushing's syndrome are often misdiagnosed as PCOS, with misdiagnosis occurring in about half of cases. These challenges highlight the importance of not relying solely on symptom observation. Instead, targeted hormonal testing is essential for precise diagnosis and treatment planning. Understanding these subtle differences plays a vital role in guiding effective care.

Distinguishing between PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia involves a detailed process that combines hormone testing, specific procedures, and imaging studies when necessary. While PCOS is often the initial consideration, doctors must conduct targeted tests to rule out adrenal-related causes.

Doctors start by measuring serum DHEAS to check for adrenal androgen overproduction and testosterone to assess ovarian involvement. A vital marker for adrenal hyperplasia is 17‑hydroxyprogesterone (17‑OHP). According to Dr. Mert Yesiladali:

"The most important parameter in the differential diagnosis is the basal and ACTH stimulated 17‑OH progesterone level when required in the early follicular period."

Testing basal 17‑OHP in the early follicular phase is crucial. Levels above 2 ng/mL often trigger further testing to differentiate between PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia. These results guide the next steps in diagnosis.

When hormone levels suggest adrenal involvement, an ACTH stimulation test may be performed. This involves administering ACTH and measuring the hormone response. In individuals without adrenal hyperplasia, only a slight rise in 17‑OHP and androgens is expected. However, in cases of non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NC‑CAH), there’s a significant increase, with even higher levels seen in classic forms. A 17‑OHP value over 10 ng/mL during this test typically indicates NC‑CAH, though newer research suggests a lower threshold of 5.4 ng/mL may reduce the need for stimulation testing. If results remain unclear, genetic testing becomes the next step.

When hormone tests leave room for doubt, genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis. Most cases of non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia stem from 21‑hydroxylase deficiency, which affects around 1 in 200 Caucasian individuals. For example, genetic testing once corrected a misdiagnosis of PCOS by identifying a CYP21A2 mutation, confirming late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia. This highlights the importance of thorough diagnostic investigations.

If laboratory tests don’t provide a clear answer, imaging studies can help. Pelvic ultrasound is a standard tool for assessing ovarian morphology in suspected PCOS cases. Polycystic ovarian morphology is found in about 75% of women with PCOS, compared to 40% in NC‑CAH patients. For adrenal evaluation, imaging options include ultrasound, CT scans, and MRI. Ultrasound might show enlarged adrenal glands with a coiled appearance, while CT scans can detect nodules or adenomas linked to rapid virilization. MRI is often used when ultrasound results are inconclusive.

Certain clinical symptoms can serve as red flags. A sudden onset of severe virilization - such as deepening of the voice or male-pattern baldness - may indicate an androgen-secreting tumor rather than typical PCOS or adrenal hyperplasia. The timing of symptoms also provides clues. While PCOS often develops gradually around puberty, adrenal hyperplasia can appear at any age, even in women with previously normal hormone levels.

Differentiating between these conditions requires a careful combination of hormone tests and imaging studies. Since PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia share overlapping symptoms, a methodical approach is essential. By combining basal hormone measurements, ACTH stimulation when needed, and imaging studies, doctors can accurately diagnose and determine the best course of treatment.

Managing PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia involves addressing the underlying causes of androgen excess with tailored treatments and strategies.

Lifestyle Modifications as the Starting Point

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists highlights the importance of lifestyle changes as the first step in managing PCOS:

"It is recommended that lifestyle changes, including diet, exercise and weight loss, are initiated as the first line of treatment for women with PCOS for improvement of long-term outcomes."

Around 70% of women with PCOS experience insulin resistance, which contributes to elevated androgen levels. Losing just 5–10% of total body weight can significantly improve hormone balance and restore regular menstrual cycles. A diet focused on low glycemic index carbohydrates, lean proteins, and healthy fats helps regulate blood sugar levels, while regular physical activity - especially strength training - boosts sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG), reducing free androgens. Managing stress is equally important, as chronic stress can worsen symptoms by increasing DHEA production.

Medical Treatments

For menstrual irregularities, acne, and hirsutism, combined hormonal contraceptives are often prescribed to lower ovarian androgen production. If additional treatment is needed, antiandrogens such as spironolactone may be added, though they require close monitoring and effective contraception due to potential teratogenic effects. Metformin, commonly used to address insulin resistance, has been shown to improve menstrual regularity, waist-to-hip ratios, and vascular health markers in non-obese women with PCOS.

These treatments focus on correcting metabolic imbalances and reducing ovarian androgen production. For adrenal hyperplasia, the approach differs significantly.

In cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, treatment centers on low-dose corticosteroids like hydrocortisone to suppress adrenal androgen production and correct enzyme deficiencies. This approach directly targets the genetic cause of excessive androgen levels. Additionally, adopting supportive lifestyle changes can help mitigate the long-term side effects of glucocorticoid therapy.

For women with PCOS who are trying to conceive, letrozole has shown pregnancy success rates of 41% to 64.8%, while IVF offers live-birth rates of approximately 29%. Before prescribing oral contraceptives, healthcare providers should evaluate risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, obesity, or clotting disorders.

Since PCOS symptoms and hormone profiles vary widely, treatments should be personalized to each individual's needs. This is especially critical for the 20–30% of PCOS cases involving adrenal hyperandrogenism, which may require adjustments to typical treatment protocols. Regular follow-ups are key to fine-tuning these personalized strategies.

Both PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia require ongoing monitoring to evaluate treatment effectiveness and adjust therapies as needed. For PCOS, this includes tracking menstrual cycles, androgen levels, and metabolic indicators. Patients with adrenal hyperplasia should be regularly assessed for the effectiveness of glucocorticoid therapy and monitored for potential side effects associated with long-term use.

For more detailed information on PCOS management strategies and the latest research on treatments and self-care, visit PCOSHelp.

Weighing the advantages and disadvantages of various treatment options is crucial when managing androgen excess, whether it originates from PCOS or adrenal hyperplasia. Here's a closer look at the specifics of each condition's treatment strategies.

Hormonal contraceptives are a common first-line treatment for PCOS, effectively lowering androgen levels and alleviating symptoms like acne, hirsutism, and irregular periods. That said, finding the right formulation can take time, often requiring a trial-and-error approach.

Spironolactone is another effective option, particularly for addressing hair loss, hirsutism, and acne. It's usually prescribed after trying contraceptives. However, it demands careful monitoring of blood pressure and electrolytes and should not be used during pregnancy.

Finasteride is used for hair loss and hirsutism but comes with potential side effects, including low libido, depression, and hypotension. Similarly, cyproterone acetate has been employed to manage hyperandrogenism, though studies show it offers no greater benefit for hirsutism than standard birth control pills.

Metformin stands out for its ability to improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood sugar, and reduce androgen levels. It can also help regulate menstrual cycles, reduce hirsutism, and improve body fat distribution. For those trying to conceive, metformin may promote ovulation and reduce miscarriage rates. However, its effectiveness is most pronounced in women with PCOS linked to insulin resistance.

In contrast, treating adrenal hyperplasia requires a more specialized approach.

Managing adrenal hyperplasia centers on reducing adrenal androgen production. Glucocorticoid therapy achieves this by suppressing the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenocorticotropin (ACTH). Research suggests that medications like hydrocortisone and dexamethasone are more effective than oral contraceptives in lowering adrenal androgen levels in cases of non-classic adrenal hyperplasia (NCAH).

However, glucocorticoid treatment carries significant risks. Long-term use can lead to obesity, short stature, insulin resistance, reduced bone density, and an increased risk of fractures and cardiovascular issues. Studies in Sweden have also linked congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) to higher mortality rates, often due to adrenal crises, and a notable reduction in final height.

For women who can't tolerate or don't respond to oral contraceptives or antiandrogen therapies, glucocorticoids may be prescribed for NCAH. While glucocorticoids are highly effective at lowering androgen levels, oral contraceptives tend to be better at reducing visible symptoms like hirsutism. Pregnancy plans also influence treatment choices; dexamethasone is not advised for sexually active women due to its ability to cross the placenta. Alternatives like hydrocortisone, prednisone, or prednisolone are preferred in such cases.

When comparing treatment strategies for PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia, the differences become clear.

| Treatment Aspect | PCOS Management | Adrenal Hyperplasia Management |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Insulin resistance and ovarian androgen control | Adrenal androgen suppression and glucocorticoid replacement |

| Long-term Risks | Lower with lifestyle and hormonal treatments | Higher due to prolonged glucocorticoid use |

| Fertility Impact | Ovulation induction often effective | Hormonal imbalances complicate conception |

| Monitoring Requirements | Initial check-ups every 3–6 months, then annually | More frequent due to glucocorticoid side effects |

| Mortality Risk | Increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular issues | Elevated due to adrenal crisis |

Both PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia come with long-term challenges, particularly in terms of metabolic and cardiovascular health. Fertility outcomes also vary significantly. For instance, a Swedish study found that only 25.4% of women with CAH had at least one biological child, compared to 45.8% of a control group. In men with CAH, testicular adrenal rest tumors (TARTs) are common, affecting roughly 40%.

Additionally, both conditions can lead to psychological stress, underscoring the need for mental health support and specialist referrals when necessary. Before starting any treatment, it’s essential to have an open discussion with your healthcare provider about expectations, potential side effects, and the need for regular follow-ups. Striking the right balance between benefits and risks is key to tailoring the most effective treatment plan for your specific needs.

Distinguishing between PCOS and adrenal hyperplasia is vital for women dealing with symptoms of androgen excess. Although these conditions can appear similar, they demand entirely different treatment strategies and have distinct long-term health considerations.

Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective management. With PCOS accounting for 80–90% of hyperandrogenism cases, it’s the most common cause of androgen excess. However, overlooking other possibilities can result in inappropriate treatments and missed opportunities to address the real underlying issue. The 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) test remains the go-to diagnostic tool, as levels exceeding 200 ng/dL warrant further evaluation for NCAH.

For those diagnosed with NCAH, genetic counseling plays a key role. Since it follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, understanding its implications can influence family planning and decisions for future generations.

Treatment approaches underline the differences between these conditions. Managing PCOS often involves tackling insulin resistance through lifestyle changes, metformin, and hormonal contraceptives. On the other hand, adrenal hyperplasia treatment typically centers around glucocorticoid therapy to regulate adrenal androgen production.

It’s equally important to recognize warning signs like rapidly worsening hirsutism, severe virilization, or significantly elevated testosterone levels. These symptoms may indicate non-PCOS causes and should prompt further investigation. While PCOS tends to develop gradually over time, adrenal disorders often present more abruptly.

Both conditions require consistent medical follow-up, but the specifics of care - such as frequency and focus - vary depending on the treatment plan and potential side effects.

Ultimately, precise diagnosis and tailored treatment plans are critical for managing these conditions effectively. Partnering closely with healthcare providers ensures the best possible outcomes over the long term.

Distinguishing PCOS from adrenal hyperplasia can be tricky because the symptoms often overlap. However, specific hormonal tests can make a big difference. For instance, elevated levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) - especially after an ACTH stimulation test - are commonly linked to adrenal hyperplasia, particularly non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NCAH). On the other hand, PCOS is usually associated with high androgen levels but normal 17-OHP levels.

Additional diagnostic tools, like the dexamethasone suppression test and serum steroid profiling, can help pinpoint the source of androgen excess. Clinical signs, such as polycystic ovaries or irregular menstrual cycles, might offer extra hints. That said, hormonal testing remains the most dependable way to achieve a clear and accurate diagnosis.

Insulin resistance plays a major role in PCOS, driving up insulin levels in the body. This, in turn, can overstimulate the ovaries, leading to an overproduction of androgens (male hormones). The result? Symptoms like irregular menstrual cycles, acne, and even challenges with fertility.

Tackling insulin resistance often requires a mix of lifestyle adjustments and, sometimes, medication. Eating a well-rounded diet, staying active with regular exercise, and maintaining a healthy weight can go a long way in improving insulin sensitivity. In certain cases, doctors may prescribe metformin to help manage insulin levels and restore hormonal balance. These approaches not only target insulin resistance but also help lower the chances of long-term health issues tied to PCOS, like diabetes and heart disease.

Genetic testing is a crucial tool for diagnosing congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), as it pinpoints mutations in the gene responsible for producing the enzyme 21-hydroxylase. This process not only confirms the presence of the condition but also helps gauge its severity.

By uncovering the genetic foundation of CAH, healthcare providers can craft treatment plans that are specifically suited to the individual. These plans often involve hormone replacement therapy to address symptoms and genetic counseling to assist families with planning and decision-making. With genetic testing, care becomes more precise and personalized, leading to better long-term management for those affected by CAH.